Iaalay ko ang aking buhay, pangarap at pagsisikap sa bansang Pilipinas.

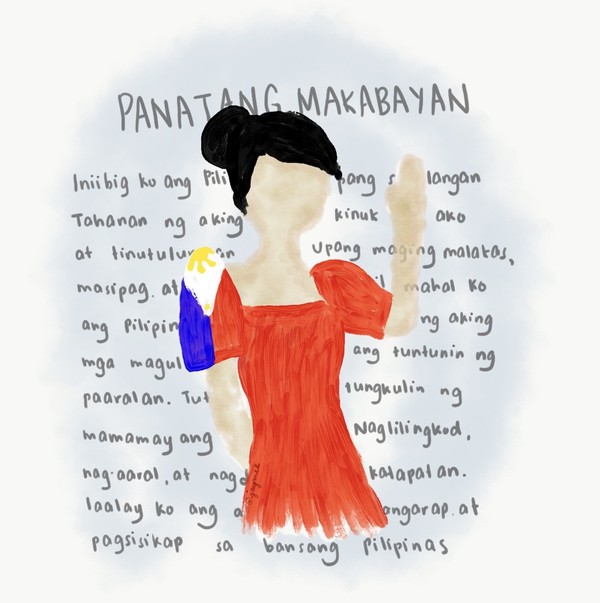

I have been thinking more and more about the national pledge that I have grown up reciting every morning before school starts. Even after five years, I still remember it perfectly. One line in particular stands out to me the most — “I offer my life, dreams, and successes to the Philippines.” This is the definition of nationalism instilled in us: the desire and willingness to serve our home country, to help it become better. I have always thought that this was a simple thing to do. Life in the Philippines is far from perfect, and I’ve dreamed of being part of the generation that creates positive change. But studying in a foreign country has given me the choice of whether to return home or to search for greener pastures elsewhere, making the notion of dedicating my life, dreams, and successes to my homeland much more complicated.

When I left the Philippines, some shook their heads, saying that I was just the latest example of the brain drain that plagues the country. I have always thought, rather idealistically, of my education abroad as a way of putting myself in a position to help, of gaining skills through resources not available to me if I had stayed home. The plan has always been to finish studying, and then to return to the Philippines to promote the need for better science education and research infrastructure. But as I approach the last years of my undergraduate education, I am forced to question whether this idea is even possible.

In the current employment landscape in the Philippines, and possibly in most other developing countries as well, there are rarely opportunities for scientists to contribute to society because of limited funding and facilities. The same goes even for other jobs; many Filipinos choose to go abroad to provide for their families, because the sad reality is that there are few job opportunities and limited financial support at home. The quality of life in the capital city of Manila — where much of the jobs are concentrated — also leaves much to be desired. Unreliable public transportation and appalling traffic conditions make life that much harder, with people typically spending up to four hours each day stuck in traffic. Even as these problems intensify over the years, the government does little to resolve them and seemingly contributes to promoting divisions within the population instead. No wonder many people, when given the opportunity, choose to leave. How are we supposed to serve the country, when the people running the country don’t even give most of its citizens the means to have a decent living?

Especially in light of the crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, I feel lucky that I am in South Korea instead of the Philippines. My life has continued as normal, with my biggest problems being deadlines and exams rather than safety and security. As I read about what is happening in the Philippines in the midst of this pandemic — extended lockdowns with no concrete plans for mass testing, exceptions from quarantine laws doled out to favored government officials, and critics of the government response being silenced or detained — I am filled with rage and guilt. Rage, that the common Filipino is not even being heard anymore, and guilt, that I feel lucky to have the choice not to go back to that system. Many Filipinos hold so much anger about how they are treated, but that anger often simmers down to defeat. In its place, there is hopelessness and resigned acceptance that things will go on exactly the way they are.

With all the political misgivings and the problems being exacerbated by the pandemic, I am left to wonder if going back home would truly allow me to be in a position to help, or if it would just trap me in a system where I have no hope for personal growth. Working towards a better society remains an idealist’s dream, because real-world situations rarely allow us to directly make lasting change. Disillusionment with corrupt systems is what prevents real change from taking root.

Iniibig ko ang Pilipinas. Aking lupang sinilangan, tahanan ng aking lahi. “I love the Philippines, the land of my birth, the home of my people.” I still have hope that I can be part of the generation that changes the status quo. But maybe, my definition of nationalism has to shift. Maybe, finding ways to help my home country even without being physically present is nationalistic enough. Or maybe, when this crisis is over, there will be enough momentum to cause a shift in society, enough to compel me to come home.