As South Korea strives for globalization in its education system, there are Western countries seeking to emulate Korea’s academically-brilliant results. In aiming for each other’s merits, are the systems bound to improve, or are they neglecting their own positives to the detriment of students in both parts of the globe? International students, both from Korea headed abroad and vice-versa, put their trust in the alternative education style offered in their new country of residence, but is it a gamble that pays off?

At home, for me, in the rural south of England, nobody has heard of KAIST. In fact, few even consider studying abroad, if they plan to attend universities at all. Partly this can be put down to the global reverence for British education, which accomplishes an inevitability in our choice — students are only informed of options within our own country. But it perhaps also demonstrates a lack of motivation in the general populace to become globally competitive citizens, further indicated by a decline in numbers of higher-level foreign language learners.

The poor standing of some significant Western nations in global educational evaluations — such as the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) — compounds a stereotype of genius Asians with whom we cannot hope to compete, much to the chagrin of the politicians who hope to boost their nation in educational rankings. In the past, Former US President Barack Obama lauded Korean academic prowess, commenting that the social norm in Korea, which regards teachers as “nation builders” and rewards them accordingly, is a policy that ought to be matched in the West. The 2015 PISA ranking in mathematics gave the stimulus behind this hope: While Korea is comfortably within the top ten, the US dipped below the average score at rank 40.

On a higher level though, the US and UK madly market the quality and heritage of their institutions, to attract international money. These somewhat romanticized worldwide reputations are a probable target of the current focus of Korean universities, especially KAIST, on globalization.

The Brain Korea 21 project, launched in 1999, was designed to increase government support of research done by the next generation of academics. The relatively recent establishment of Incheon Global Campus (IGC), hoping to become a hub of global education by opening “extended campuses” of international universities, is indicative of the increased mingling of systems. Currently, a key selling point for IGC is the financial advantage over the huge cost of gaining the same degree in the universities’ home countries.

But the Korean education system that produces phenomenal results does have its own issues: the hagwon “cram school” culture contributes to the nation’s abysmal PISA ranking in student wellbeing. So the emergence of a new system must be carefully managed to only replicate the best aspects of each to provide a benefit for all.

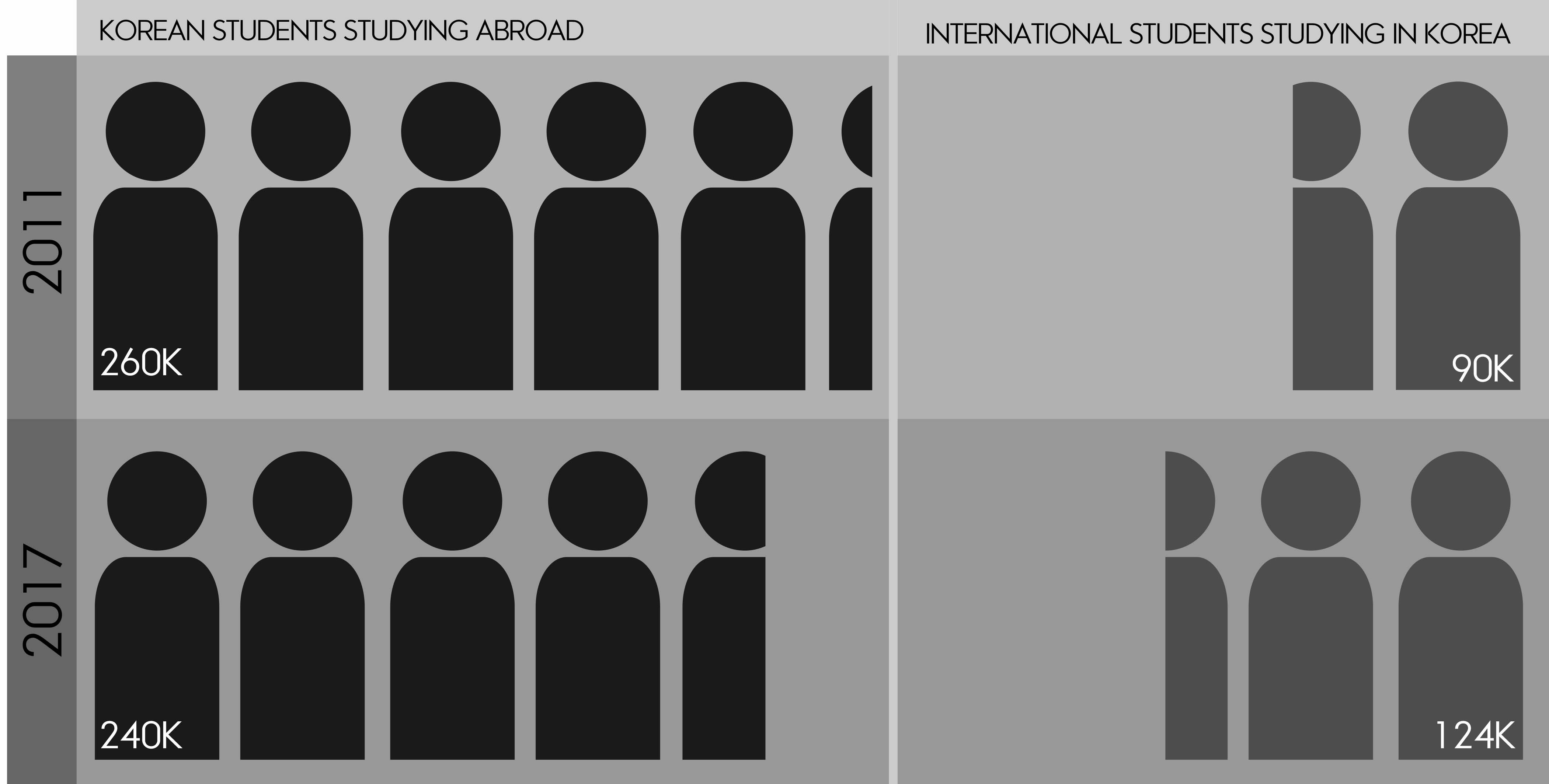

According to the Korean Ministry of Education, the number of Korean students going abroad for education has decreased from a peak of about 260,000 in 2011 to approximately 240,000 last year, with the most popular destinations being China and the US. One reason for the decline is the decreasing birth rate leading to a shrinking pool of students. But another factor is the consideration that as top Korean universities become more globally significant, the cachet of studying abroad is not necessarily giving graduates an edge over homegrown job contenders. While there is no doubt that experience of another culture is a point of interest for employers, in Korea, this carries less weight than it used to.

By comparison, the number of international students at Korean universities is steadily increasing, reaching 124,000 in 2017. As the Korean Wave picks up speed in the West, it piques the interests of its young audience; meanwhile, the youth select their educational options. The attraction especially of KAIST with courses offered in English and the future promise of a bilingual campus mean that it seems inevitable that more Westerners will begin to come here. Though, for now, it seems I will remain the sole representative British undergraduate!