North Korea

A couple of days before Christmas, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) announced the successful launch of its long-range intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM), with its leader Jong-un Kim issuing a statement that both threatened and reassured the world. Jong-un Kim declared that North Korea was now capable of striking the entire continental US with nuclear weapons, but would never attack first as the nuclear option was merely a deterrent against US military aggression. This was consistent with the political strategy and rhetoric that North Korea had been espousing since the start of its regime.

But, before delving into what the future holds for the Korean peninsula, I would first like to discuss nuclear proliferation in general and why the world, particularly the US, is intent on disarming North Korea.

The Beginning

After the atomic end of WWII, nuclear weapons took center stage during the Cold War between the US and the Soviet Union, with the terms “mutually assured destruction (MAD)” and “nuclear deterrence” entering political discourse. Unable to directly engage in war with one another, the two aggressors started several proxy wars, which included the Korean War, and amassed massive stockpiles of nuclear weapons. With the impact of nuclear weapons looming over the world, several other victors of WWII began development of nuclear weapons of their own, namely the UK, France, and China.

Proliferation

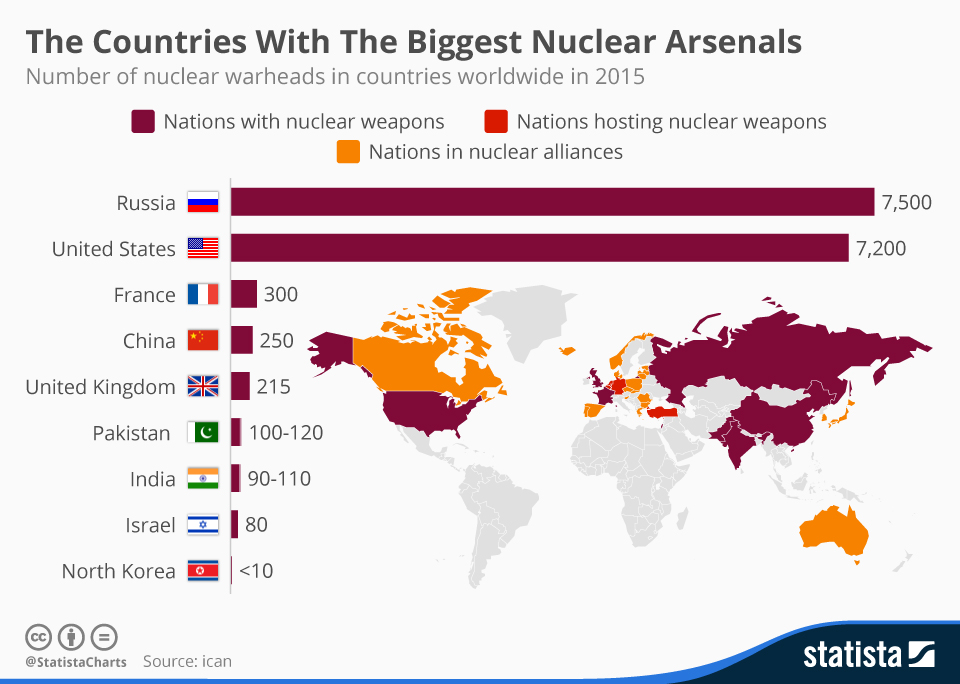

From the first atomic bomb dropped on Japan, nuclear weapons have created a chain reaction in national defense and politics across the world. There are currently nine countries armed with nuclear weapons, four of which (India, Pakistan, Israel, and North Korea) are not signatories of the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT). The NPT began in 1970 when the first five nuclear-armed nations (US, Russia, UK, France, and China) created an international treaty that aimed to prevent the creation of more nuclear weapons, pursue nuclear technology only for the sake of harnessing energy, and eventually disarm all countries of nuclear weapons. Since then, the four aforementioned nations have acquired nuclear weapons, Iran is still on the edge of following suit, and the original five nations show no sign of disarmament.

Israel has always maintained a stance of deliberate political ambiguity regarding nuclear weapons, but most experts believe that Israel has developed nuclear arms with technological help from Britain and France. In addition, CIA reports have confirmed that the US has known about Israel’s nuclear development since its early stages. India revved up its nuclear weapons technology after a turf battle with the nuclear-armed China, while Pakistan followed suit after similar dealings with India. Initially, both countries faced sanctions and criticism by the US and international bodies for nuclear proliferation, but for economic and political reasons, all sanctions were eased and the US is now a staunch ally of India and Pakistan, adopting the unofficial position of accepting India and Pakistan as nuclear-armed states.

So why has the US, and most Western powers, accepted India, Pakistan, and Israel but not Iran and North Korea? Perhaps it is simply due to the fact that the US sought out allies in Asia that would counter the growing Chinese presence in the region and decided to abandon its NPT-driven foreign policies in favor of increasing its sphere of influence. North Korea has long been a friend of China and Russia, which may further explain the US’s urgency to solidify the case that North Korea should not be allowed to develop nuclear weapons. After all, China continues to renounce India’s nuclear weapons while implicitly turning a blind eye to North Korea’s own developments for the most part.

To some, this double standard on nuclear weapons imposed by the victors of WWII may be old news. But in light of the recent progress made by North Korea in terms of nuclear weapons capabilities, I thought this might be a good time to question the politics of nuclear armament, open discussion on why North Korea should (or should not) develop its own nuclear weapons, who are trying to stop it and for what reasons, and how the future looks for the Korean peninsula and, by extension, the world.

Back to North Korea

I have always been in the minority when it comes to the politics of North Korea. To me, there is no difference between a nuclear-armed Pakistan or US and a nuclear-armed North Korea. I have never believed that North Korea would use its nuclear weapons unless attacked first and I have always spit back at the hypocrisy of the US anytime it intervenes and prevents other nations from developing nuclear weapons (as it has done on countless occasions, namely Taiwan, Japan, South Korea, Germany, etc.). The point of nuclear armament is deterrence and if even one nation acquires the technology, others will inevitably follow suit. Either all nations relinquish the weapons, a new technology appears that will neutralize nukes, or most nations eventually become armed. I tend to bet on the latter two options on the basis of my limited knowledge of human nature.

Nonetheless, for better or for worse, I believe that the so-called “North Korean problem” has been more or less solved. Unless there is an unbelievably stupid accident, I don’t think the situation will escalate any further, despite the current media fanfare and fiery political rhetoric. Politically and diplomatically, North Korea will end up like India or Pakistan as most nations will begrudgingly and unofficially start to accept the presence of nuclear arms in yet another non-NPT country. And the behavior of North Korea seems promising.

A couple of days ago, in a surprisingly timely political move, North Korean leader Jong-un Kim threatened that the nuclear button is always on his table while announcing that North Korea is willing to participate in the 2018 Pyeongchang Winter Olympics held in South Korea. The two warring nations reopened hotline communications for the first time since December 2015, and South Korean President Jae-in Moon welcomed high-level diplomatic talks. With the US out of the way, perhaps this could signal the first North Korean step towards normalizing relations with the South as well as with the rest of the world. To echo the cautious wise words of the Commander-in-Chief of Twitter, “I don’t know. We’ll see.”