Books have been the medium of storytelling for generations, with imagination driving the reader to become an active observer in the unfolding narrative, themes, and characters. The reader is forced, by the nature of bound paper, to read between the lines; black text and white spaces are the only visually creative tools that are afforded to a reader. The author can only do so much to evoke the descriptors in the readers’ minds. Conversely, films and television shows dramatically flip that medium by engaging viewers through the ears and eyes. A glaring absence of text and a massive screen dominates the film-producing and film-going experiences. The visual and auditory elements take the responsibility of imagination from the reader and place it squarely on the shoulders of filmmakers. Every face, scenery, color, sound, and design feature is carefully selected and presented to the audience.

In general, the audience of a film will see, hear, feel, and think all the things that the director, screenwriter, and cinematographer want the viewer to. We are not given much space and time in our minds to process the characters, themes, and stories at our own pace and way before the camera cuts to the next scene. Of course, this is all in the intrinsic nature of film; but at times, there is the occasional film that stirs the imaginative gears in my head into action like reading a good book.

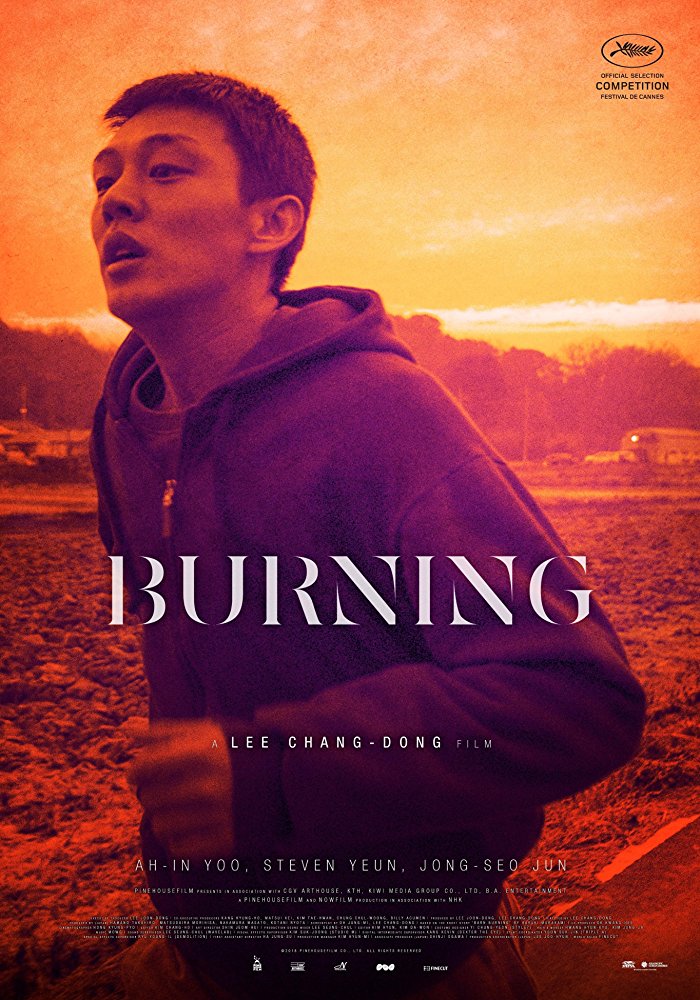

As a fairly recent example, I want to focus on Lee Chang-dong’s latest film, Burning. It has been a while since I watched a film that made me pause as significantly and as profoundly as this film did. Not because it executed the recognizable aspects of “art house” or “auteur” films excellently, but because I felt like I was forced to “read between the lines” and utilize my imagination at the cinema. The blended adaptation, of William Faulkner’s main character in Barn Burning and Haruki Murakami’s plot in Barn Burning (same names, two completely different short stories) by Lee created a masterpiece of storytelling that purposely leaves the audience with much to process. It is one of the few times I’ve seen an adaptation where I would actually recommend people to not read the original sources and watch the film instead, or at least, first.

One of the most intriguing aspects of this film is the adaptation of the main protagonist Jong-su. His external personality is vaguely based on the third-person view of Colonel Sartoris Snopes in Faulker’s Barn Burning while the first-person narration provided by the film’s source material, Murakami’s Barn Burning, is largely missing. This mixed adaptation of a single character, who is the only point-of-view protagonist in the movie, results in an emotional experience that feels unusually distant and impersonal. This layer of intrigue is brilliantly enhanced by the way his character in the movie maintains a blank look on his face that leaves much for the audience’s imagination. The moviegoer is forced to project their confusion, thoughts, and feelings onto a face that is rather expressionless and devoid of the reactions and emotions we expect to see.

The other, more obvious narrative device used by Lee was to simply hold back information as much as possible from the audience. The film shows us how Jong-su follows Ben — which tells the audience that Jong-su suspects Ben as the culprit behind the disappearance of Hae-mi — but the film does not directly give the audience any solid information. This tool for imagination is, of course, a necessity for mystery thrillers such as this, but the inclusion of scenes that are mainly silent — with Jong-su running or working on his computer — provides enough time for the audience to process and interpret the story while enhancing the general ambience of mystery. The slow build-up of tension as the plot gradually thickens is complemented wonderfully by the increasing confusion provided by Jong-su’s reticence and the lack of supporting information to explain his behavior. And since this entire unreliable narrative is shown through his eyes, the audience has no choice but to formulate their own ideas of the story and characters, which are starkly left to the imagination once the rather abrupt twist ending concludes the film.

The mystery of the film is not Ben or the disappearance of Hae-mi. The mystery lies with the characters, especially Jong-su. Each character perfectly rides the lines between quiet insanity and driven action; between obscure paranoia and confident revenge; and between melancholy emptiness and shallow amusement. And we utilize our imagination, reading between those lines and becoming an active participant of the story.