Countless relics were plundered by European countries during colonial rule. Western museums continue to hold these relics, which are of immense historic and cultural significance to former colonies. Should these artifacts be kept where they currently are, or should they be returned to their rightful owners?

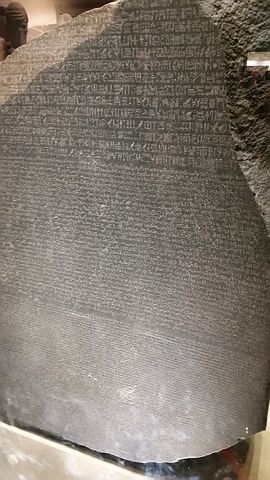

The Rosetta Stone, one of the most valuable Ancient Egyptian and Greek bilingual texts and an instrumental tool in deciphering hieroglyphic scripts, is currently on display in the British Museum. Plundered by Napoleon during his campaign in Egypt, it was taken from the French when they lost the war against Britain. Egypt has requested repatriation for the stone several times, first in 2003 and later in 2005. These requests were met with overwhelming opposition from national museums. In a joint statement issued by the Pergamon Museum in Berlin, the British Museum, the Louvre, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the following passage can be found: “Objects acquired in earlier times must be viewed in the light of different sensitivity and values reflective of that earlier era… museums serve not just the citizens of one nation but the people of every nation.” In 2005, the British Museum presented Egypt with a full-sized fiberglass replica, but the Rosetta Stone itself still remains in the British Museum.

The question of artifact repatriation remains controversial today. While most people agree that repatriation is the moral thing to do, the benefits of repatriation are almost always short-term compared to keeping things where they are. The artifacts may do more good for humanity as a whole if they remain in these museums. After all, museums are encyclopedic; they store records of the entire human race in an easily accessible manner. Museums in cosmopolitan cities are more ideally located and thus attract more visitors, from researchers to tourists. The British Museum welcomes an estimate of five million visitors every year. Return the Rosetta Stone to the Cairo Museum, for example, and it would enjoy only two million visitors annually. These artifacts also enjoy much better protection in these museums. Not all countries are well-equipped to protect and preserve historical artifacts — Egypt, for example, struggles to protect its pyramids from vandalization.

Museums also allow for the universal exchange of art and relics. In what is known as “collection exchanges”, museums exchange arts and relics to each other, allowing a greater opportunity for audiences to enjoy the art works. These exchanges also benefit curatorial research and international relations. Additionally, since art can be seen as universal, a collection of art from different locations and time periods may offer greater insight into the culture and history of humanity. As an example, The Metropolitan Museum of Art houses thousands of ancient artifacts from Africa, Oceania, and America. Together these relics show the history of the entire human race, and not of any single nation state. Furthermore, artifacts belonging to an ancient nation state, culture, or people no longer belong to any particular modern nation. So the relics of ancient China, for example, may be too far removed from modern Chinese culture to be considered the property of China.

Encyclopedic museums are also the first step towards globalization. By removing the national borders of history, the human race can be seen not as separated nations but as a united whole — undivided by borders or conflicts. Only when all history is seen as history of the human race can there be complete unity amongst ourselves.

While allowing big museums to keep the artifacts is safer and more practical, it is undeniable that this arrangement profits only the museums and is unfair to the countries where the artifacts were taken from. Alternatives to repatriation to address this issue include sharing the museum’s profits with the home countries, or making the artifacts more accessible for citizens of the origin country to visit and see. In these cases, repatriation won’t be necessary, while the income can go to bettering the country and helping its people — a win-win situation.