The recent Joseon Exorcist became the first ever K-drama to be cancelled after just two episodes after public outrage against its distortion of history. This leads to a broader question of how historical TV shows should deal with history itself. Do historical shows bear an extra layer of responsibility to portray history accurately, or are they mere fiction, after all?

Since the invention of the television, gone are the days when entertainment was limited to operas that only the upper class could afford. Operas cost quite a fortune centuries ago, and — of course — you had to pay for every single show. Television, on the other hand, is a one-time purchase and is a shareable service we can use anytime. With the help of online video streaming services such as YouTube and Netflix, watching television programs become even more convenient. And in this way, television has become an almost universal form of entertainment. But to maintain this universality, sensitive programs should be either banned or heavily censored. The question then boils down to what’s considered too sensitive for television broadcast — and this is where things get murky. When expensive opera was the mainstream, the target audience of plays was more or less homogeneous: wealthy local aristocrats with similar mindsets and interests. But these days, mainstream television show crews have to consider audiences from all sorts of genders, ages, and backgrounds. In order to reach a global audience, even the most mature late-night series shy away from topics that may trigger the majority of the world.

Unfortunately for TV producers, we still seem to find just about every scene problematic. In the case of Joseon Exorcist, its crew seems to underestimate Koreans’ respect for their historical figures and Korea’s tension with China. Most Western viewers would probably be oblivious to the historical context of Joseon Exorcist, but this is exactly what Korean viewers are concerned about. And to be fair, it is indeed a valid concern, for a casual Western audience might learn a distorted depiction of Korean history after watching the series.

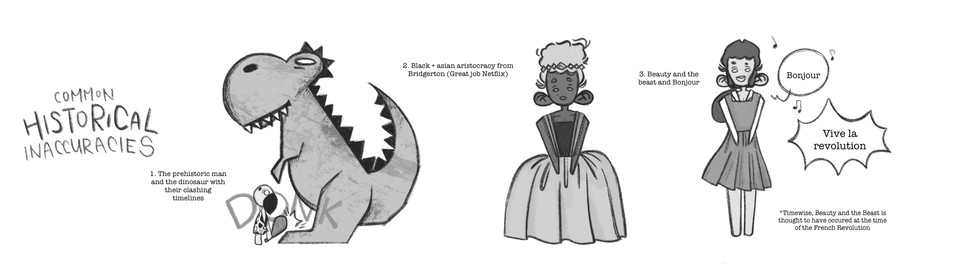

But let’s examine the controversy again. Joseon Exorcist never claims to be a documentary — it is a historical fiction. Rather than its historical setting, the fact that it is, nevertheless, still a fictitious story needs to be emphasized. Sure, the creators of the series should have been more aware of the sensitivity of the issue, especially considering Korea’s current tensions with China over cultural assets. However, is it wise for anyone to learn history from fictional works in the first place? At best, fiction should only be seen as a medium to introduce viewers to history, not one to replace the role of history classes and textbooks. Instead of assuming that the real-life King Taejong was a cruel tyrant after a few episodes of Joseon Exorcist, viewers should have looked for more legitimate historical sources. In this day and age, this information is only one Google search away. Is it really fair to put all the blame on the show producers when us viewers are the ones who should have done more research?

Perhaps another way to see it is that, instead of using the names and backgrounds of real-life, revered historical figures, the makers of Joseon Exorcist could have replaced the characters with fictitious counterparts, while preserving the historical setting. Perhaps this would have mitigated the backlash to some degree, but I’m sure some would still criticize the series nevertheless. Alternatively, the writers could have based their story on less influential people instead, as the kings featured in the series are indeed some of Korea’s most respected figures. But if these principles are the absolute rules for any historical series, we won’t be able to see creative what-ifs about major events and figures in the past, and all we are left with are documentaries for history classes. Television writers and producers are not the only ones disadvantaged here — this kind of “rule” will limit the history we can experience from series we watch as well. Let’s be honest — when is the last time you watched a purely nonfiction documentary?

Just like in other forms of media, universality in television comes at the expense of artistic freedom. The fact that visual entertainment can now be accessed by almost everyone means that almost everyone can find fault in the contents as well. While producers are responsible for predicting how audiences will respond to their work, this is nothing but a temporary fix. In this rapidly changing global era, the target market of television shows, along with what’s considered appropriate and not, will always evolve. Instead of blaming the media for what we see, it is time to start holding ourselves accountable for how we consume media.