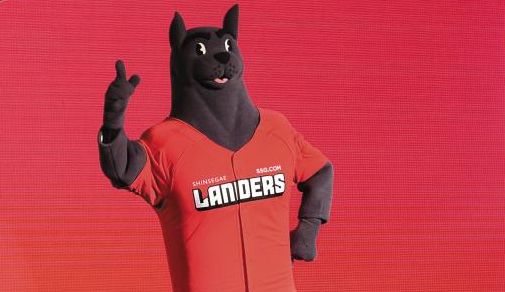

Baseball, without a doubt, is the most popular sport in Korea. Packed stadiums (during the pre-COVID era), home runs, and the offseason drama are all enough to excite fans and draw them closer to the sport. This January, baseball fans in Korea received one of the more shocking offseason news in recent years: SK Telecom sold the SK Wyverns to Shinsegae, renaming the team into the SSG Landers.

The sale of the SK Wyverns not only surprised fans but also those in baseball. Yes, the sale of a baseball club isn’t unprecedented; one can recall the sale of the nine-time Korean Series champion Haitai Tigers to Kia Tigers, or the more recent disbandment of Hyundai Unicorns. But such sales and disbandment largely took place due to the financial struggles of the teams’ corporate owners, whereas SK was doing just fine. This sale happened as the SK Group was shifting its sports policy from supporting professional sports like baseball to supporting less popular, amateur sports, in accordance with the company-wide policy of focusing on social impact initiatives. This alone was not enough to disband the team, which would result in public outrage. But when Shinsegae sought to buy a baseball team, common interests were met, and SSG Landers was born.

Most teams in the Korea Baseball Organization (KBO) (as well as most professional sports teams in Korea) are owned by large corporate conglomerates, hence the company-based team names such as Samsung Lions and LG Twins. This lies in stark contrast to the city-based team names of Major League Baseball, such as the Boston Red Sox (how weird would it be if they were called the John Henry Red Sox?). And as you may expect, the finance of the teams rely heavily on support from their corporate owners. Operating a baseball team is not cheap; from player payrolls and stadium maintenance to hotel fees and spring training camp costs, it is realistically impossible to cover these expenditures solely with basic sources of revenue such as ticket sales and broadcasting deals — even more so during the pandemic. The financial support from the corporations was what allowed the teams to barely break-even. KBO teams on average would have recorded a loss of 5.7 billion KRW last year if it wasn’t for their corporate owners.

Then why do the corporations continue to operate baseball teams? The reason was more political than anything else in the beginning. But what kept them in the league is likely the advertisement opportunities. A baseball game on average is three hours long, and during this time fans are continuously exposed to various ads, such as team names and corporate products embroidered on uniforms. Less direct but perhaps more powerful, fans associate the brands of the companies with their respective teams, and have a more favorable view towards the companies, especially if their team performs well. There are reports that Kia received 200 billion KRW worth of advertisement effect when the Kia Tigers won the Korean Series back in 2009. Aside from economic reasons, there may be the owner’s pure love of baseball. Taek-jin Kim, the CEO of NCSOFT and the owner of NC Dinos, is known to be an avid baseball fan. Shinsegae’s Vice Chairman Yong-jin Chung is known to be a sports fan as well. For these multi-billionaires, owning a baseball team may be like owning a limited-edition luxury sports car.

Despite these reasons, the trend is clear. The time when corporations single-handedly carried the teams financially has passed. In 2014, Samsung moved the Samsung Lions from its core division to Cheil Worldwide, its smaller marketing division. The sale of SK Wyverns signifies the extent of the trend. There have even been rumors that another KBO team offered to sell to Shinsegae (but Shinsegae refused as they preferred a team in the metropolitan area). This indicates that more corporations may be seeking to step aside from baseball, and if common interests are met, future sales are just as likely. One reason for this trend may be that corporations are valuing less and less of the advertisement benefits from baseball, particularly because they are already famous enough. No one ever said, “hey Samsung Lions is a good club, oh wait, Samsung’s a company, oh wait, they make phones too?”

As many firms move away from the frontlines of baseball, some advocate for the sustainability of baseball teams in Korea. The Kiwoom Heroes is without a major corporate owner (Kiwoom Securities only owns the naming rights). The club managed to successfully achieve sustainability with naming right sales, player sales, as well as traditional sources of revenue. Clubs like the Samsung Lions and the Doosan Bears are also reducing expenditures in an attempt for some sort of sustainability. There can be other creative means of business with baseball. Shinsegae, having recently acquired SSG Landers, is reportedly planning to build a dome stadium and incorporate it into a large shopping mall, which is similar to the cases of the Tokyo Dome or the Truist Park in Atlanta.

What will the future of baseball in Korea be? My personal prediction is that the current corporate-ownership model will continue, partly because things tend to stay as they are, and partly because baseball will always remain popular. Companies would not simply disband their teams out of nowhere, as the public repercussions will trump any expenditure they may save from the disbandment; if they do sell, that means there was another corporation ready to take on the daunting task. Aside from all the uncertainty, one remains a constant for baseball fans: baseball will always start in spring and a wave of emotions will follow, no matter what the team name may be.