The 2020 Tokyo Summer Paralympic Games marked its end on September 5. Over 4,400 athletes representing 163 countries participated in 23 different sports, including archery, badminton, equestrian, wheelchair basketball, wheelchair fencing, goalball, and powerlifting. This was a record number of participants competing in more than 500 events.

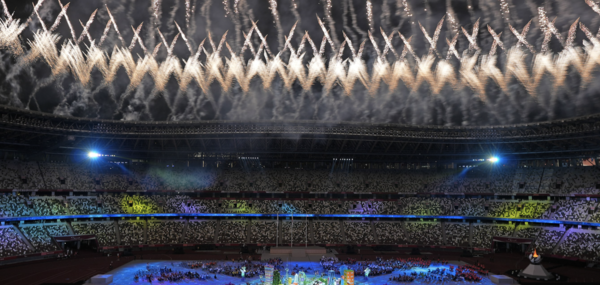

The Tokyo Paralympics hold greater significance than just the increase in the number of participants. The International Paralympic Committee (IPC) launched the “WeThe15” campaign during the closing ceremony of the Games, which aims to end discrimination against people with disabilities. The “15” stands for the 1.2 billion people with disabilities, who constitute 15 percent of the world population. Backed by the IPC and the International Disability Alliance (IDA), “WeThe15” will initiate positive change for the marginalized 15 percent especially through sports, which provides a powerful tool for engaging massive audiences globally. The closing ceremony projected a short clip with the following message: “persons with disabilities must be seen, heard, active, and included.” Speakers in the promotional clip added that “before the Paralympic flame is extinguished, it will pass its light to a new movement,” provoking anticipation towards this new campaign.

The launch of a campaign promoting values of disability visibility, inclusion, and diversity seems very timely. Although two years have passed since the IPC’s 30th anniversary in September 2019, there have been few noteworthy improvements in the public’s attitude towards disability and the general treatment of the Paralympics as a non-mainstream event.

Lack of media coverage has been a longstanding issue in the Paralympics. The Mainichi, Japan’s National Daily, reported that the Japanese public broadcaster NHK provided 1,000 hours worth of Paralympic events. However, commercial broadcasters merely scheduled 20 hours dedicated to wheelchair basketball and swimming. MBC and SBS, two of the three major broadcasting companies in Korea, allocated 16 hours and 10 hours, respectively, to live broadcasts of the Paralympics — only about one-tenth of the total air time allocated for the Olympics. These broadcasts were scheduled for noon and late evenings, which are time slots with generally low ratings. Despite the diversifying forms of media and gradually increasing media coverage of the Paralympics, its size is yet incomparable to that of the Olympics.

Along with the quantity of media coverage, the quality of media content featuring the Paralympics still remains questionable. The portrayal of Paralympians in news articles and social media has failed to divert from the “supercrip” or “triumph over tragedy” narratives that herald athletes as “heroes” who have “overcome” their disabilities. These narratives are problematic in several ways. First, they draw attention to the disability of the Paralympian rather than the athletic performance that should be highlighted. By framing Paralympians as heroic beings who accomplish an unlikely success in spite of their disabilities, many disabled individuals experience the “achievement syndrome” and feel unrepresented. Furthermore, these narratives reinforce the view that disabilities parallel a state of defect and incompleteness that needs to be overcome to achieve “normality,” strengthening a very ableist notion.

“Inspiration porn” is another prevailing narrative. According to Stella Young, a disability activist, inspiration porn shares one or more of the following characteristics: evoking sentimentality and pity, conveying a moral message primarily towards a non-disabled audience, and objectifying disabled people anonymously. One common example is associating inspiration and hope with the Paralympics, despite other paramount Paralympic values such as courage, determination, and equality. Paralympians are reduced to subjects of inspiration and admiration for coping with their mental or physical condition, which is an inevitable consequence of a society centered around the non-disabled. Not many news articles induce readers to find inspiration in Paralympians’ actions and attitudes rather than in their disabilities.

Exploitative views towards disability are still prevalent and mainstream. It is unclear specifically how “WeThe15” will incite change in people’s attitudes towards disability. However, it is definitely necessary given the perpetuating social problem of ableism. Moving forward, the campaign must achieve a highly idealistic goal: eradicate the public’s underlying assumption of incompetence towards people with disabilities.