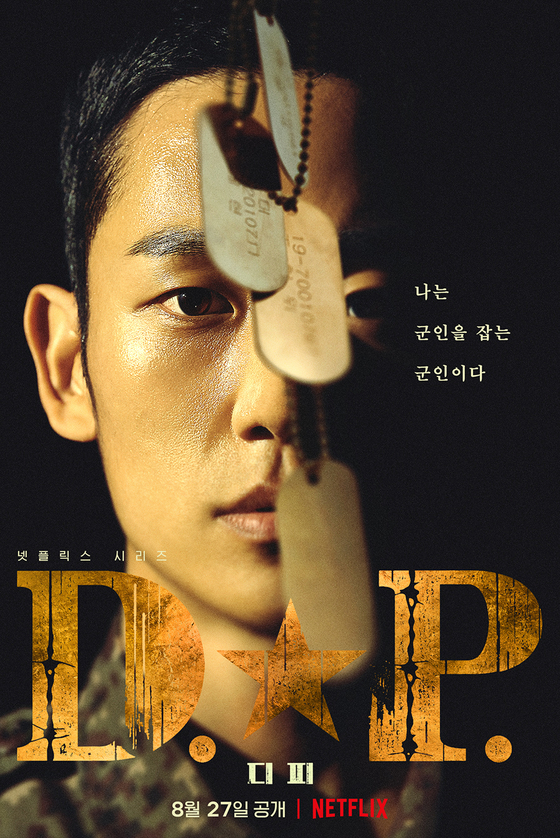

Every Korean man that once stood under the sign “Korea Army Training Center” has heard it: “Everyone goes through it; why shouldn’t you be able to?” D.P., a Korean Netflix original series based on the webcomic D.P.: Dog’s Day, reveals the dark side of Korea’s military culture that has always been overlooked as something “everyone goes through.” The show follows Private An and Corporal Han on their missions to capture those that refused to bear the weight of this normal and deserted their sacred duty. Warning: this review contains spoilers.

In the shadows of South Korea’s unbelievably rapid technological growth, rainbow-colored K-pop culture, and skyscrapers that line the urban skyline lie the remnants of the Korean War that ended only 70 years ago. The price of our forefathers never having found a middle ground has been passed along the generations and has now come down to the sons of those that have not even been in war themselves. With the conscription system still in place, young South Korean men between the ages of 18 and 28 take 18 months from their best years to serve the country for close to nothing in return.

Unfortunately, the “close to nothing in return” is not the worst part of the 18 months (which even then is a reduced number of months from the 21 in 2014, when D.P. is set). For some, living the notorious hierarchical structure is the war itself — an unrealistic world where what shouldn’t be real is considered normal — and D.P. portrays but few of those battles. While the law treats deserters as war criminals, it does not take the whole six episodes for the viewers to realize that most deserters are the victims, only without a perpetrator. Some leave to escape normalized bullying, while another to support a sick and old family member with no one else to depend on. In most incidents depicted by the series, the deserters are those who decided to protect themselves as a means of survival, as no rule or law would do so for them.

The biggest case Private An and Corporal Han chase after at the climax of the series successfully sums up the ultimate question the series throws us: “Why can’t the military change?” Private Cho, a calm and caring person by nature, surrenders to rage after months of atrocious bullying by seniors and decides to take revenge. But when he fails and sees that he has no way out, he takes his own life in front of the unit of soldiers surrounding him. Though it was partly a resignation from realizing how far he’d come, greater was his fear that nothing would change for future Private Chos. Surely enough, though the duo solved various cases throughout the series, none were followed by a long-term solution from the military — the authorities dealt with problems by covering them up like they were never there, rather than resolving them. Despite Private An’s desperate persuasion, offering to help change the system, Private Cho only points out that even the water bottle he was provided dates back to the Korean War. Knowing too well that the twisted system stood firmly in its place for so long for a reason, he leaves but a few words before pulling the trigger: “Someone must do something.”

The series comes to an anticlimactic yet once again bitterly realistic ending, where Private Cho’s case is reported on the news as a horrendous incident caused by a compulsive soldier with “issues”. It is true that the Korean military system, especially for the conscripted, has been improving in some parts. Pays have almost tripled over the last four years (though still nothing close to minimum wage), mobile phones are now allowed outside working hours, and service duration has been reduced. However, rather than thinking of these changes as “welfare”, we must be outraged that these basic rights have never been guaranteed until now, as the precious years of young men in their 20s and their labor are still being taken for granted. For those of us remaining complacent with what is considered normal, D.P. is like medicine — painful to take in, but good food for thought.