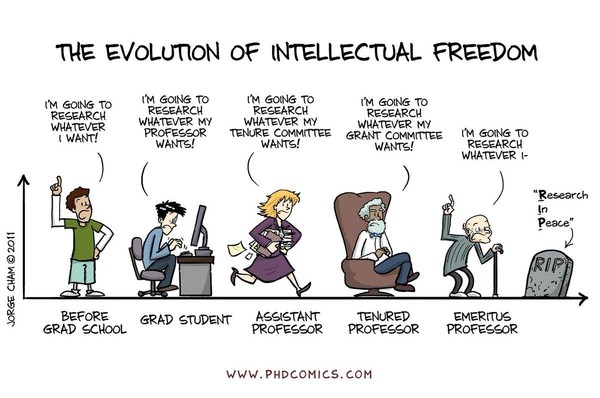

It does not take long to convince the average person of the bad side of corporate — capitalism, greedy power-tripping elites, illegal labor, you name it. For STEM students and researchers, there is basically only one alternative career: academia. Compared to its industry counterpart, working in academia presents a utopian façade to unsuspecting young students. Aspiring new academics often decide to pursue a career in academia because they do not want to partake in the exploitative practices of corporations, or because they want to study what they are truly passionate about. They believe that academia embodies the true purpose of science: pushing the limits of human knowledge and making discoveries for the betterment of society. It is not completely false, but as they go further up the academic ladder, they realize that there is more than meets the eye.

Just like corporations and just about any other things in life, academic research runs on money. No matter how grand or noble an idea might be, no research can be done without funding. The struggle for funding eventually becomes a breeding ground for unhealthy competition, as countless academics are vying for a handful of grants from a few public and private organizations. In order to make it into the recipient list, academics sometimes resort to backstabbing and other unethical conducts. While it is almost impossible to come up with a breakthrough invention alone, the need to constantly become “the best” and “the first” in order to be worthy of research grants punishes collaboration. Two intelligent brains are better than one, but what if the collaborator steals the idea or leaks it to their own colleagues, sabotaging the other's research plans?

The problem is, the never-ending race to be the best is not only motivated by funding, but also by status. Even with funding and ingenious ideas already on hand, academics still need to fill in a list of metrics. A researcher’s worth is quantified by their number of citations, how many and where they publish, i10-index, h-index, and several other numbers. All of this information is publicly available and easily searchable, making it all too easy for academics to compare themselves to their peers. In order to get to the top, professors have to pump out as many papers as possible, hoping that a few would “catch on” and finally earn them a name in the field. This system seems to reward abusive practices such as forcing graduate students to work nonstop and pressuring peers to write one’s name in a published paper, even if they hardly contribute to it. We have often heard about the slave-like conditions of graduate students, but in reality, professors are also slaves to this system that dehumanizes brilliant minds into mere numbers and statistics. While unethical, these behaviors are sadly often ignored because they are deemed necessary for an academic to stay relevant in the field. The moment one stops churning out publications, their academic career is over — a phenomenon infamously dubbed “publish or perish”.

The publish or perish culture ironically harms the quality of academic research as a whole. The pressure to attract a large number of citations seemingly discourages innovation, as it is a much safer bet to spend resources on follow-up studies to established papers or trending topics. While hopping on saturated subjects might not garner too many citations, they are much less risky than exploring novel topics that are still largely unknown, and thus prone to failure and less likely to be funded. Some risk-taking is necessary for breakthrough research, but if the research is unproductive for too long, the researcher will lose their funding and publication goal.

Unfortunately, the difference between a “useless” and “breakthrough” research is sometimes only down to luck. For instance, Katalin Karikó, whose lifelong work on mRNAs became the foundation for Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna’s COVID-19 vaccines, was largely unknown for a majority of her life. She used to be ridiculed for her “weird” research and struggle to find grants, but suddenly she was showered with awards and praises after the pandemic stroke and the need for her work arose. For every happy ending like Karikó’s, there are thousands of other potential works that are collecting dust because no demands for them ever appear in their lifetimes. Because of this, a majority of academic papers are not necessarily made with the interest of humanity in mind, but with that of funding and prestige. Can we still say that academia purely acts for the sake of science if competition is more important than humanity?

Once an academic earns recognition, all doors are open to them. But in the meantime, they have to put up with unsteady funding, unhealthy working environments, unoriginal work, and underpayment, among many others. At the end of the day, the problems in academia are just as bad as those in industry, if not worse. Some people, like Karikó, still decide to follow their passion at the expense of a stable career. The rest choose to temporarily set aside their values, believing that they will be able to atone for it once they get “big”. How much are you willing to compromise “in the name of science”?