“History repeats itself,” goes a quote often repeated by anybody vaguely familiar with past and current events. An authoritarian populist gets elected president? Hey, I’ve seen that before! A territorial war breaks out in Europe? Been there, done that! A plague spreads like wildfire and puts the whole world at a standstill? Not the first time! If one listens to the armchair historians, one would think that everything happening now has already happened before. Yet, as much as one hears about the repetition of history, the words “unprecedented times” get thrown around just as easily. With thousands of years of history at our disposal, how is there anything left without precedent to surprise us?

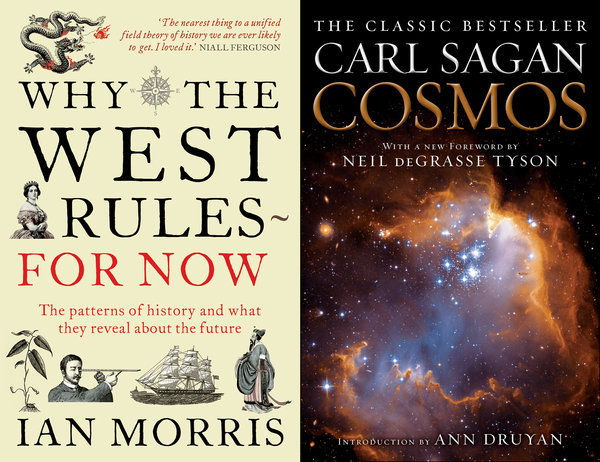

I’ve recently come to ponder this question not just because of everything going on in the world right now, but also because of some books I’ve been reading. Cosmos, by Carl Sagan, delves into the history of the universe so far: from the Big Bang and the formation of the stars and planets, to the beginnings and evolution of life and the rise of human civilization and where it goes from here. Another book, Why the West Rules — For Now by Ian Morris, involves a more compact time period, exploring the early days of humanity until the modern era, where Western civilization seems to have an advantage over the rest. These two books are highly educational reads, but together, they hammer home one point: there is so much more history than we commonly think about. History — in the broadest sense of the word, that is, “everything that has happened in the past”, rather than the academic sense of “everything that has been written” — is so vast that it would be impossible to know and remember it all, which is why every person only ever learns and recalls bits and pieces of it. And, as is human nature, every person thinks the parts of history that they do know are much more important and significant than the parts that they don’t know.

But that’s not true. Because, in the first place, we don’t get to decide what we know and don’t know. We learn about history in school, in books, and these days even on social media. School curriculums, however, are often decided by governments; books are written by people with agendas; and social media is a whole different can of worms with its influencers and algorithms. This is not to say that there is no truth, that everything we see is filtered or fabricated. Sure, there is a lot of fake news out there, and from one source, we can learn only part of the historical truth at best. No source ever gives you the whole story, so you need to go through all the effort of pursuing the truth from multiple sources — and nobody has the attention span for that anymore.

Thus, we’ve arrived at a point where the entirety of recorded history is right at our fingertips, and all we have to do is dig a little deeper. Even if we did, though, how much would it actually help? The actual quote goes, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” But times change, and circumstances are never completely the same. There may be some similarities because, after all, some things are constant in the universe — whether it be the laws of nature, or human nature — but there are so many factors beyond our control that shape history. In his book, Morris makes a point about how geographical, environmental, and technological factors, rather than individual decisions, made the biggest impact on how human civilization progressed. Humans are reactive creatures: we simply respond to the immediate present, not to all of history. And that hasn’t stopped us before — human nature hasn’t changed much, but the human race has collectively made so much progress in the brief cosmic blink of an eye that we have existed.

History will always be there, and it cannot be erased. Sagan lamented how much progress we lost when the Library of Alexandria was burned down. Yet now, the information accessible through a single smartphone could dwarf an entire library’s worth. He remained optimistic about the inevitable direction of progress, that we will eventually come together as one species and reach new worlds. History may not be linear, but it is cumulative. So there is reason to be as optimistic as Sagan, even if many of us seem uninterested in history. To paraphrase Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., the arc of history is long, but it bends towards progress.

So what is there to learn from history? Maybe nothing, after all. History is a tree in the woods — it will make a sound, whether there is anybody around to hear it (or refuse to hear it). Everything that happens is unprecedented because events are dictated by universal laws that our feeble minds cannot possibly comprehend. Sure, the past is worth trying to understand, and there is value in learning it. But with or without our knowledge or permission, history will march on. Perhaps it’s time for us to humble ourselves and recognize that we don’t make history — history makes us.