Elections All over the World

A succession of parliamentary and presidential elections have been observed all around the Americas, Asia, and Europe in the first half of 2022. In this Spotlight, we seek to analyze the trends that pervade through the recent elections.

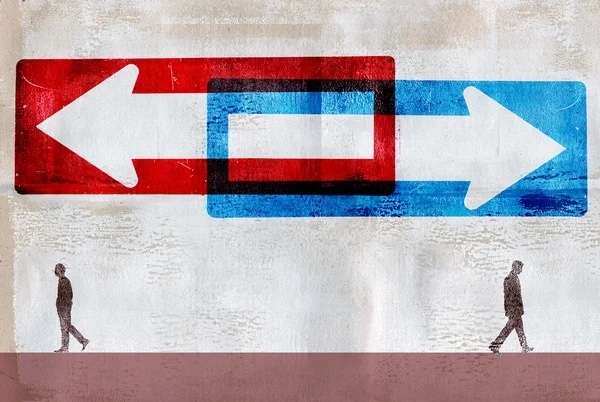

The dynamics of elections around the world are becoming more and more difficult to predict. The close French presidential race between Emmanuel Macron and Marine Le Pen confirmed the rise in right-wing populist sentiment in Europe; Latin America is continuing to turn toward the left, with Gustavo Petro taking the lead in the Colombian elections; and Ferdinand Marcos Jr.’s triumph marks uncertainty for democracy in the Philippines. Choosing an individual to represent and lead a country is a decision that may change one’s life for an average of four to six years. Voters thus naturally select the candidate who lays out pledges that suit their best interests. But what happens if none of the options given to the eligible voters align with their values or desired policy changes? As political standpoints of candidates in presidential elections are seemingly becoming more polarized, a middle ground is diminishing.

The divide between political parties is often pointed to as the primary cause of political polarization. As groups of people with similar political ideologies, political parties often attempt to distinguish themselves from one another by minimizing the overlap of constituencies, particularly during election periods. Where the candidates are essentially competing for one position, the goal of each is to secure their share of voters.

While a healthy level of political differences is expected and even essential in maintaining a variety of opinions within a democracy, many recent elections have shown a stark clash between the pledges of the two main contenders. Looking at the French elections in April, Le Pen suggested bold reductions in prices and taxes, along with drastic nationalistic measures to advantage French nationals in comparison to foreigners. On the other hand, Macron seeked progressive diminishing of taxes and minimum wage raises, criticizing that Le Pen’s pledges are “authoritarian” and would be unable to be funded. A similar tendency was also observed between Lee Jae-myung and Yoon Suk-yeol in the South Korean presidential election in March, where it was difficult to find any topic that the two main contenders agreed on. It is also interesting to note that some pledges in the Korean election were not even necessarily based upon the traditional “progressive” and “regressive” ideologies of the Democratic Party of Korea and People Power Party, respectively. With the increase in polarization, apart from those who clearly fit the target group of a particular candidate, voters are forced to determine which of the extremes would benefit them slightly more.

Another issue is that the “us versus them” mentality tends to become exceedingly pronounced during elections. With the formation of a rivalry, usually between the two prominent parties, political campaigns become focused on revealing the opponents’ flaws not only in terms of political agenda, but also of their personal history. During campaigning for Costa Rica’s elections in late March, candidate Jose Maria Figueres questioned now-president Rodrigo Chavez about his sexual harassment accusations, and Chavez responded, “[Figueres] campaign as you govern, with dirt and lies,” on a televised debate. These types of personal attacks taking place as a status quo in election strategies acts as a further segregator between parties.

Furthermore, the reducing enthusiasm for elections could perhaps be attributed in part to political polarization. As the political parties divide, an increasing number of citizens do not identify with any particular party. A “satisficing” phenomenon thus occurs: people vote not for who they think is most well-qualified to lead the country, but for the lesser of the two evils, meaning that they are not necessarily satisfied with any of the candidates. This was highlighted in the South Korean elections in March, where the media often portrayed the rivalry between candidates Yoon and Lee as a race between the “unfavorables”. The lack of interest in the presidential candidates was also demonstrated in countries such as France, where voter turnout was the lowest in two decades. In the long run, weak support for the elected president could have a negative effect on the stability of the government and the nation as a whole, since people may be more easily disillusioned by any shortcomings of the government.

As politics become more extreme, elections have effectively become the process of weighing between the two opposites. Of course, this is not to imply that convergence toward the center is beneficial — it must be acknowledged that the policies candidates look to implement are bound to be different as they have varying visions for the future of the country. Nevertheless, posing an opposite stance just for the sake of differentiating themselves from other candidates is counterproductive. An ideal election should consist of candidates and parties expressing their views uninfluenced by other contenders. Though this may not be possible in reality, it remains that democracy should be established upon a spectrum of opinions that does not limit voters to a choice between one extreme or the other.