Elections All over the World

A succession of parliamentary and presidential elections have been observed all around the Americas, Asia, and Europe in the first half of 2022. In this Spotlight, we seek to analyze the trends that pervade through the recent elections.

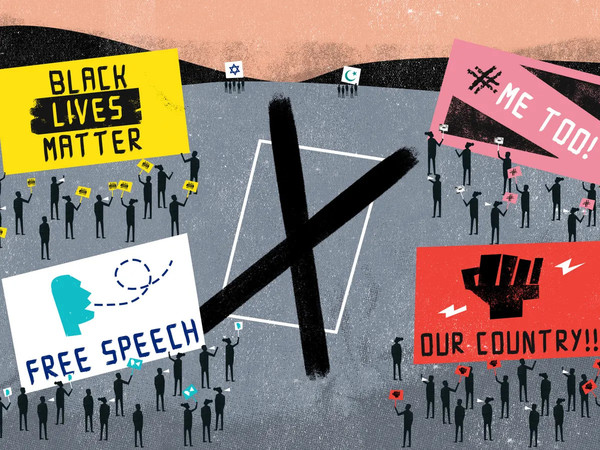

Identity politics refers to the tendency for people of a particular race, religion, ethnicity, or culture to form political alliances based on these identities without regarding the interest or concerns of any larger political group. Identity politics emerges when groups that have been historically ignored or oppressed demand their rights to be protected, from civil rights or women’s rights, to LGBTQ+ rights. This helps individuals to have a more secure sense of self and social belonging. It also propels disadvantaged minorities to counteract inherited negative stereotypes, defend more positive self-images, and develop respect for members of their groups.

Identity politics is increasingly baked into politics. Even if candidates from different parties try to avoid it, voters are increasingly divided by identity, which remains salient to their choices at the ballot box. Therefore, identity politics is becoming both an electoral and a governing strategy playing an important role in elections. A case in point is the April presidential election in France. Marine Le Pen from the Rassemblement National Party, running against Emmanuel Macron from La Republique En Marche, appealed to the native French people by pledging that if elected, the country will dramatically reduce immigration and fight Islamicism — for instance, by making all Islamic head coverings such as hijabs illegal in public. Along the same lines, Le Pen proposed to abolish the droit du sol (a law allowing children born in France to foreign parents to automatically obtain a French citizenship when they reach the age of 18), enforce stricter laws to access French citizenship through marriage, and expel foreign individuals who have not worked in France for more than a year. With France becoming a more heterogeneous society with an increasing number of migrants gaining permanent citizenship, Le Pen’s pledge was estimated to turn over more than 3.5 million people’s votes in France. Although it cannot be concluded that identity politics caused the defect of Le Pen, it certainly took part in the election.

Identity politics do not only pertain to race. In South Korea’s most recent presidential elections, different candidates tried to appeal to different age groups and gender using identity politics. In Yoon’s pledge, he claimed to abolish the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family because he believes that the need for the ministry has disappeared as a gender-equal society has already been established to some extent. Meanwhile, those who are against the pledge, such as the Korea Women’s Associations United (KWAU), believes that the ministry is essential to decrease the gender gap in employment and wages and protect victims of sexual and domestic violence. This pledge resulted in a stark difference in votes by gender among the 2030 generation. Among votes from men in their 30s, candidate Yoon accounted for 58.7%, while candidate Lee only made up 36.3%. In contrast, among women in their 20s, candidate Lee attracted 58% of the votes while candidate Yoon reached only 33.8%. The same pattern was observed for people in their 30s. Therefore, while Yoon succeeded in winning the support of young men, female voters turned their backs.

The idea of identity politics started by believing that safeguarding human rights makes society fairer, more tolerant, and more equal. However, some now think that these protections have gone too far. By focusing too much on their own rights and interests, they threaten the rights of others. Today, countries are divided around identities rather than policies, which makes constructive democratic dialogues more difficult. This is because every time somebody of one identity wins, everybody in the other identity believes that they have lost something profound. Democracy needs the capacity for compromise, and turning everything into an identity issue makes it very hard to do so. To prevent identity from becoming weaponized, politicians can talk more about actual policies and aim for reasonable consensus instead exploiting identity divides and trying to appeal to specific groups.