My mom has been utterly selfless since the day she gave birth to me, her newly careerless lifestyle composed entirely of giving rides, cooking, and cleaning.

As grateful as I am for this, most of us would agree that a mother’s complete selflessness may be excessive. I used to attribute my mom’s unhesitating altruism to her personal standards. Perhaps even the Korean norms instilled in her while she was brought up. But after reading up on some literature recently, I realized that gender roles might have also been influenced by a long history of politics, reinforced in our minds through pretty words on dog-eared pages.

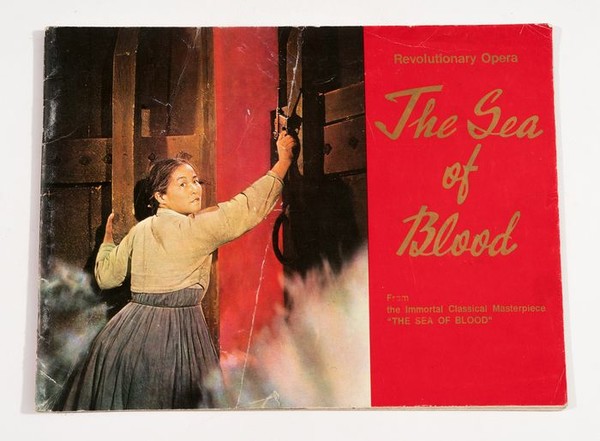

A clear case of gender politics in literature can be seen in North Korea. Sea of Blood by Kim Won Kyung is an established anti-Japanese revolutionary classic widely known in the country. The story, set in the 1930s, follows a mother who leads a revolution for North Korea against the Japanese colonizers. Though the classic’s “official” purpose is to display the nation’s unity against imperialism, publicizing the tale was arguably a tool for the administration to plant the deep-rooted ideal of the complete sacrifice of the individual for the interest of the collective.

North Korea’s glorification of “motherhood” in a largely patriarchal society can be deemed thus an intentional choice. Sea of Blood portrays its protagonist mother as the strong leader of a revolution through jarring imagery of weaponry and of radical uprising. When viewing the mother, words like “leader,” “power,” and “hero” come to mind. But why did North Korea choose to personify a heroic figure through a middle-aged, common-folk female character? Wouldn’t this just empower more citizens to rebel?

I asked the same questions –– and there seems to be something deeper. While a mother is a universal symbol of tradition, in Sea of Blood, the plot positions the mother as the resistance. Interestingly, considering that colonizers aim to undercut tradition and force new values onto the colonized, a protagonist who rebels against colonizers is by virtue rebelling by upholding tradition. In other words, this co-existence of change and tradition within the mother emphasizes that maintaining tradition is actually a way of revolution. In this sense, North Korea cleverly redirects the rebellious instinct in human beings into feelings of rebellion that sides with North Korea instead of against it.

A deliberate alteration of what it means to be a “revolutionary subject” — in the context of the extreme country of North Korea, my analysis can’t help but seem a little far from our everyday lives. Perhaps a look at a famous dystopian novel, set in 1992, should offer an additional perspective. Phillip K. Dick’s novel (that later inspired the blockbuster movie Blade Runner), Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, describes a similar phenomenon. In the novel, civilians practice the religion of Mercerism by entering a digital simulation while pelting rocks at the “god” of Mercerism. The characters regard this as a way of “cleansing the soul”. Some critical readings of the novel have pointed out that, in the totalitarian world of Do Androids Dream, Mercerism and its practice is a way for the government to allow civilians to vent negative feelings in the simulation, thereby letting the subjects exhaust their instincts of rebellion within bounds that are fictional and therefore containable. By doing so, civilians are led to believe they are truly free to think, speak and act, while an everyday practice insidiously controls them.

The Orwellian tactic is not just a reality in North Korean popular literature but all around us. Take the concept of motherhood, for example. Allegories like French Marianne, Mother Russia, and Inang Bayan (translating to “the motherland” in Filipino) allude to motherhood as a way to ingrain feelings of nationalism. East Asian societies, where Confucianism upholds family-centric ideals, have synonymized the idea of motherly duties with unconditional sacrifice. In social media, there are lobbyists left and right who support the idea of traditional mother roles under the excuse that embracing is a part of the feminist movement. Now, I don’t for a moment suggest that all ideas about motherhood have been carefully crafted by a “Big Brother” with an ulterior motive. I do, however, believe it’s worth a thought — what made our parents so selfless? Were any of those ideals conceived in the subconscious?