Known for mind-bending films such as Memento and Inception, as well as the critically and commercially successful The Dark Knight trilogy, Christopher Nolan is one of only a few directors in Hollywood whose name alone could convince people to buy a movie ticket. The status that Nolan holds among film aficionados and casual moviegoers alike signifies the confidence and trust that he has built through his years as a filmmaker. In short, the name Nolan has become synonymous with quality.

And Oppenheimer delivers. Released on August 15 in Korea, almost a month after it was released worldwide, Oppenheimer is the culmination of Nolan’s 25-year filmmaking career. It is a three-hour biopic — neither a superhero movie, a sci-fi epic, nor a thrilling war film. Yet, even those with only a passing familiarity with Nolan’s work will notice the many elements present in Oppenheimer that bear similarities to his previous films.

Before Oppenheimer, Nolan had never written and directed a biographical film. The closest thing would have been his 2017 film Dunkirk, which depicted the events of the evacuation of Dunkirk during World War II. Oppenheimer is the first film in which Nolan focuses solely on the life of a person who actually existed. It’s no surprise, however, that J. Robert Oppenheimer, the theoretical physicist who acted as director of the Manhattan Project, caught Nolan’s attention. In 2012, The Dark Knight Rises featured a thermonuclear bomb as a plot device, while Tenet, Nolan’s most recent film before Oppenheimer, references the father of the atomic bomb by name. Nolan’s status among his generation of filmmakers mirrors the regard in which scientists held Oppenheimer at the time: while both are widely recognized as reliable, brilliant, and natural talents, neither had won the highest honors in their respective fields (Oppenheimer never won a Nobel, and Nolan has yet to win an Oscar).

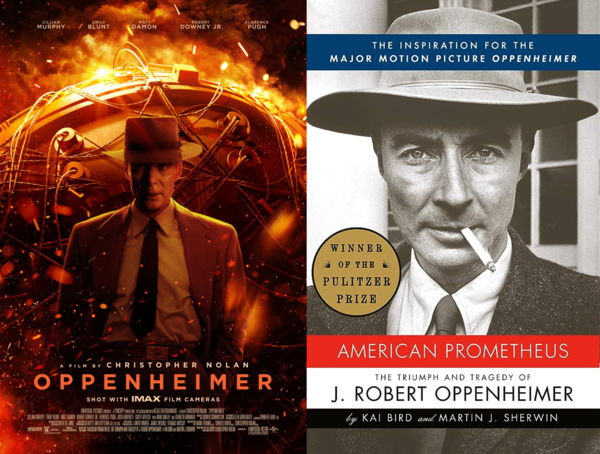

The reference material for the film is the biography written by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin, American Prometheus, which won a Pulitzer Prize in 2006. An extensive, well-researched book, it details the life of Oppenheimer, from his childhood, his early years as a student and scientist, his involvement in the Manhattan Project, until his death. It also delves into the lives of the people closest to him: his family, his mentors, his lovers, and his colleagues. However, in calling his film Oppenheimer, Nolan signifies his intention not to adapt American Prometheus in its totality but only to focus on one character. The script, in fact, was unconventionally written in first-person, which emphasizes that the film is mostly presented from Oppenheimer’s perspective.

This meant that, while the movie has a star-studded cast of A-list actors portraying historical figures, the success of the film hinged on one particular performance: that of Cillian Murphy. A known actor and regular Nolan collaborator, Murphy had never been the lead of a Nolan film before. Yet, his supporting roles in Nolan’s previous work and his starring role in the drama series Peaky Blinders showcase his mastery of acting, which led Nolan to consider Murphy as his first and only choice. Murphy carries the weight of the whole film on his back, making the audience believe that he is Oppenheimer and all of his external brilliance and internal conflict. Other standouts include: Robert Downey, Jr., whose portrayal of antagonist Lewis Strauss demonstrated his acting prowess after a decade of being known for Tony Stark; Emily Blunt, who expertly embodies Oppenheimer’s wife Kitty, an intellectually brilliant, emotionally resilient woman stuck in the role of housewife; and Tom Conti, who plays the distinguished and jaded Albert Einstein, a minor role with a major part.

Aside from some familiar faces like Cillian Murphy, Gary Oldman, and Kenneth Branagh, Nolan also employs techniques in Oppenheimer that he had used before. For instance, the use of color and black-and-white as a visual shorthand to differentiate between two narratives is also seen in Memento. The recurrent jumping between different time frames is a tool Nolan is also fond of; even with straightforward material like the life of a real person, Nolan still resorted to his penchant for nonlinear storytelling. This may be confusing for some moviegoers at first, but Nolan routinely uses visual and verbal cues to guide viewers into understanding the film’s chronology.

On the other hand, Oppenheimer also falls into the common drawbacks characteristic of Nolan’s work. For instance, Nolan is not exactly known for his ability to write female characters well; most of his movies, in fact, grant the main (male) character a dead wife or girlfriend for motivation. Unfortunately, Oppenheimer did not have a dead wife in real life; still, Kitty’s character mainly stays on the sidelines for much of the film, with her one standout (dare I say, Oscar-worthy) scene mostly taken word-for-word from a transcript of the hearings that stripped Oppenheimer of his security clearance. Another regular criticism of Nolan’s films is the sound design: the dialogue in his films often is drowned out by background noise, sound effects, and the musical score, and Oppenheimer is no exception. For such a dialogue-heavy film, it is sometimes hard to make out what the characters are actually saying. And, even at times one could listen properly, the dialogue can be too flat or heavy-handed, another characteristic of Nolan’s writing.

Despite those drawbacks, Oppenheimer remains one of Nolan’s best works. With strong source material to support his writing, Nolan could focus on what he does best: the technical aspects of filmmaking. Nolan utilizes the scale of the IMAX format better than any other director. The sets are stunning, the costumes realistic, and the visual effects superb. One scene even showcases Nolan’s ability to create suspense out of something as simple as a speech in front of an audience. Nolan is a director first, a writer second.

But perhaps the strongest aspect of the movie is the effect it has on the audience after leaving the theater. A three-hour biographical film heavy on dialogue and light on action is not the biggest box office draw, yet Oppenheimer transcended those limits to ask people important questions. Was Oppenheimer responsible or naïve? Did the creation of nuclear weapons make the world safer or more dangerous? And what would you have done if you were in his position at the time? Unlike the IMAX film used to shoot almost half of the movie, the answers aren’t quite as black-and-white as one would expect.