“I could never be of both worlds, only half in and half out, waiting to be ejected at will by someone with greater claim than me. Someone full. Someone whole.”

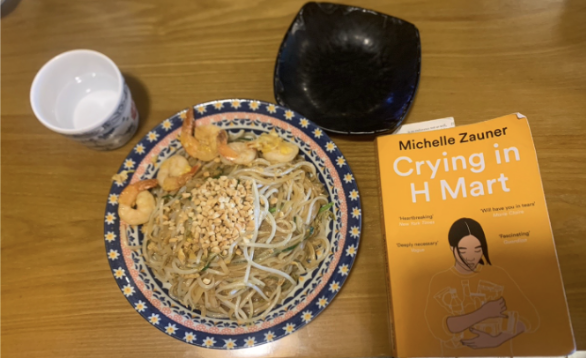

I received this book in a paper bag parcel from Tallo, my half-white, half Asian — “Wasian '' — college friend. The Asian-American book recommendation and The New York Times Best Seller Crying in H Mart by Michelle Zauner was postmarked from Japan to my American home, and timely packed into my suitcase for reading while studying abroad in Korea.

Michelle Zauner is the Wasian, Korean-American lead singer of the shoegaze band Japanese Breakfast. Crying in H Mart is her first written publication detailing her experience dealing with her Korean mother’s passing from pancreatic cancer. It is a telling of the complex intersectionality of ethnic connection, mother-daughter relationships, and their lasting effects framed against death. The book is known as a well-known go-to for anyone vaguely interested in reading non-fiction adult literature, but notably touching diasporic members of East-Asian communities.

I grew up in the Korean-American festered streets of New Jersey, a typical American gyopo: American-born, ethnically Korean, but per the locals, “out-of-touch”. While spending my exchange semester and eating in Korea, I consumed Michelle’s award-winning memoir. Alone at the Busan train station, at KAIMARU, and at a coffee shop in Dongdaemun — every time I opened this book in public I ended up crying because I could not effectively wrangle the overwhelming, raw emotion that marinated each chapter. And yet, I give it a 7 out of 10.

Crying in H Mart suffers from “college essay syndrome” – a glorification of suffering. Zauner’s praised style of “making the ordinary appear beautiful”, can, if poorly executed, convey a self-important author tone. The day-to-day journalistic style marked with a self-lamenting position, yet absent of a greater motif, aimlessly drags simple ideas to great importance. It tackily detracts from allowing the experience to state itself.

Although filled with performative romanizations and a forced, cookie-cutter plot, this only marks the first few opening and closing chapters of the book. The center filling of the piece is a cathartic, sincere, and uncalculated recounting of personal, mundane, and traumatic scenes that tug a personal connection to the reader. The most striking scenes are those of vulnerability.

Zauner speaks to the developing complexity of filial piety, and how over a lifetime, the role of caretakers phases and blurs. To some, especially in East Asian cultures, a family is an extension of self. Whether it be in social status or whatever afflictions that plague them, a family’s member’s outward success and suffering is felt internally. When Michelle’s mother is in hospice, the stringent, image-conscious woman at the start of the book has now slowly whittled to one who cannot speak, one who cannot eat, one who cannot even tend to the bathroom without assistance. Michelle steps into the caretaker role for her caretaker, acting as an extension of her mother as her mother once did for her. She spends sleepless nights next to her, desperately cooking Korean food to convince her mother to eat, and grasping at her Korean heritage before her familial connection to it passes. To be tethered that closely to someone can create a visceral, selfish love that overwhelms us in sickness and grips us in health. No matter how the illness of a family member can appear to rob us of humanity, it cannot rob the remnants left from living, which include the love they gave you. The dignity that remains with family outlives the limitations of human life.

No one’s story ever gets tied up neatly in bows. That’s reserved for fiction, for something that mirrors real life — not something that is a recounting of one. Michelle tries to convince the world of her mother’s death’s significance, to the significant depth it affected her. Through this, she searches for a resolution she could not find in the misfortunate, abrupt end of her relationship with her mother. However, I wish Michelle didn’t feel that she needed to have a reason or meaning clearly stated in her story, because there is value in just sharing your story as it is.

In the end, Crying in H Mart is a fun read as opposed to a well-composed one, a good book rather than a good story, despite Michelle’s best efforts. I feel it would have been an even more effective memoir if it was honest in its nature, rather than force-fitting a plot template over her personal story. My feelings toward Michelle Zauner are my feelings about my heritage, my mother, and myself. Gangly and awkward with a discomforting distaste in it, but at the same time, with a charming, familiar comfort. It is an homage to not being “Korean enough”, but that is what makes her, her.