The Ukrainian Crisis, A Political Tightrope

Although a single country, Ukraine is divided by contrasting views on the current crisis. The cause for such divisions within Ukraine is not simple - the divisions go back much further than the recent events. Since the collapse of the USSR in 1991, Ukraine has been torn into the east and west.

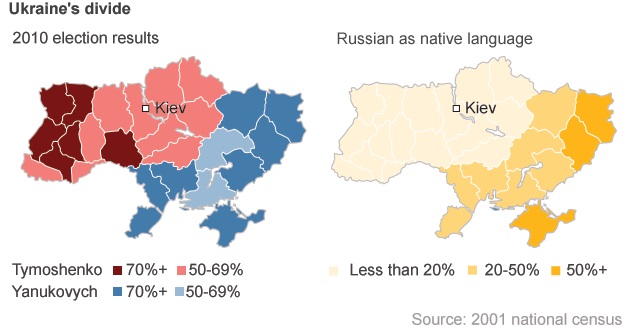

This divide has been reflected culturally and linguistically until today. Russian is widely spoken in parts of the east and south. It is even used as the main language in some areas, including the Crimean peninsula. On the other hand, the western regions – closer to Europe – speak Ukrainian as the main language. Like Ukraine, the Autonomous Republic of Crimea also shows diverse ethnic and cultural background. Crimea was transferred from Russia to Ukraine while under Soviet rule in 1954. As a result, ethnic Russians make up about 58% of the entire population, while Crimean Tatars are estimated at 12%. Previously in 1944, Stalin accused Crimean Tatars of collaborating with the Nazis and deported them to Central Asia, and more than 250,000 have returned since the late 1980s. The rest of population of the peninsula are Ukrainians.

Such divisions in Ukraine and the Crimean peninsula are reflected in recent responses to the crisis. On March 16, 97% of voters in Crimea have supported a proposal to join Russia in Crimea’s secession referendum. Such referendum is designed to show public endorsement for the decision. Soon after, Russia’s President Putin, Crimea's Prime Minister Sergei Aksyonov, the Crimean Parliament’s Speaker Vladimir Konstantinov, and Mayor Alexei Chaliy of Sevastopol, signed a treaty on making the peninsula a part of Russia.

The Crimean Parliament gave its official position on the referendum that stated the need to protect Crimeans from “extremists” that came to power in Kiev, and now threaten their lives and the right to speak Russian. The parliament elected a pro-Russian prime minister and voted to break away from Ukraine. Speaker Konstantinov said that the referendum was merely a matter of "legalizing" an opinion that was already known. He said on Ukrainian television, "There will be no surprises. Do not even hope."

The Russian Parliament said that it would respect the result of the vote. Putin said the referendum is “based on international law,” further supporting the referendum. After the vote, Putin signed a bill to absorb the peninsula into Russia. In a televised address in front of the houses of parliament and Crimea’s new leaders, Putin said, “Crimea has always been and remains an inseparable part of Russia.” The referendum had been legal and its results were “more than convincing […] The people of Crimea clearly and convincingly expressed their will – they want to be with Russia.”

In contrast, the interim government in Kiev, the capital of Ukraine, argued that the referendum is illegal, and the referendum was only set in order to legitimize the presence of Russian troops in Crimea and its annexation to Russia. Kiev called for a boycott of the vote, and Ukraine’s interim president, Oleksandr Turchynov, annulled the Crimean Parliament’s decision to hold the vote and pledged to disband the republic’s legislature. Furthermore, the interim government has issued arrest warrants for the Crimean Parliament Speaker Konstantinov and Prime Minister Sergei Aksyonov on criminal charges of attempting to take state power.

After the bill was signed, Kiev said it would never accept the treaty. The Ukrainian foreign ministry said, “We do not recognize and never will recognize the so-called independence or the so-called agreement on Crimea joining the Russian Federation.” Furthermore, Ukraine’s interim Prime Minister Arseniy Yatsenyuk said that the Crimean crisis had moved from the political to the military stage, emphasizing the severity and the urgency of the crisis.

Interestingly, this is not the first time that Ukraine has had such contrasting perspectives toward a vote. The cultural and linguistic divisions were also to some extent shown in the voting patterns of 2010 election between Ukraine's currently ousted president, Viktor Yanukovych, and the heroine of Ukraine's Orange Revolution, Yulia Tymoshenko. The areas where a significant proportion of the people speak Russian almost exactly match those that voted for Yanukovych, who expressed open support for Putin, in the 2010 elections. Considering the long and complex history of cultural, racial, and linguistic divisions in Ukraine and the strong influence of Russia over Ukraine for decades, experts say that this crisis will not end with the referendum in Crimea.

Seung Hyun Suh

hyunsuh@kaist.ac.kr