Increasing the admission quota for medical schools is an unresolved dispute that has been distressing the South Korean government. On one hand, it seems that South Korea does need more medical students, as many rural areas and vital sectors are deprived of doctors and suffering from a healthcare shortage. On the other hand, the fundamental solution to these issues might not be to increase the population of doctors; doing it without a systematic plan may result in the decline of healthcare quality and end up achieving nothing meaningful. In this month’s Debate, we discuss whether expanding the quota for medical schools is the best option South Korea has.

Medical schools hold a seemingly aristocratic status in South Korea. Exceptional, distinguished, elite — these are only some of the words that describe the dream of many parents and students in the country. Since 2006, 3,058 aspiring doctors have been entering this prestigious fortress every year.

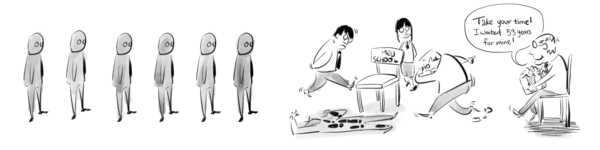

With the government’s official announcement of its plans to expand the admission cap for medical schools scheduled in the near future, the Korea Medical Association (KMA) is expressing its fierce resistance for the second time since 2020, when they organized a general strike and pushed the then government to settle with a neutralized agreement. The doctors have once again warned that they won’t be idle about the government increasing the number of medical students, hinting at the possibility of another strike in case their demands get rejected. However, have they proposed a better option than the one supported by the government, medical schools, and more than 70% of the citizens?

Put simply, South Korea needs more doctors. Despite its standards of health care services outstripping most countries in the world, South Korea has only 2.5 doctors for every 1,000 people, placing it second to last among the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries and far behind the OECD average of 3.7 doctors per 1000 people. South Korea’s older population is growing faster than almost every other OECD nation, so without scaling up the infrastructure starting now, we won’t be able to respond to the accelerated, inevitable increase in the need for medical services.

Moreover, the undersupply of doctors is more keenly felt by those in rural areas where access to medical services is much more arduous to get. There are great discrepancies in the amenable mortality rate between the capital and noncapital regions, meaning that people living outside Seoul and Gyeonggi Province are more prone to death due to a lack of timely medical treatment. To bridge this gap, the only possible and effective initial step at this point is an absolute increase in the number of doctors when redistributing the population of doctors that is already concentrated in capital areas is virtually impossible.

Consideration also needs to be made regarding the disparities in the number of doctors across different professions. Specialties like dermatology have traditionally been popular in South Korea, while the number of doctors in “vital” sectors such as thoracic surgery is on the decline. Although fundamental solutions will have to be implemented to resolve this dynamic between doctors working in different fields, the first step is to increase the currently meager quota so that there is at least a possibility of doctors in such unpopular domains increasing.

The professors at national medical schools are confident that their educational infrastructure can currently support an increase in the number of medical students, and healthcare workers deeply feel the lack of labor force in the field. Unless the KMA gives an alternative that resonates with people, their claim that increasing the number of doctors is not the fundamental solution to the status quo will not echo.

Doctors are no longer in the prestigious fortress. They, too, like other citizens, are members of society doing work that is valuable to the nation. This means they do not earn a pass to threaten citizens to go on strike or exclude other healthcare professionals from discussions that will impact the entire society. The desperate need for increasing doctors is too palpable for people to compromise with ambiguous reasoning at this point. The doctors’ stance shouldn’t be to persevere with their argument, waiting for the government to surrender, but to find a middle ground that considers the overall welfare of society.