Increasing the admission quota for medical schools is an unresolved dispute that has been distressing the South Korean government. On one hand, it seems that South Korea does need more medical students, as many rural areas and vital sectors are deprived of doctors and suffering from a healthcare shortage. On the other hand, the fundamental solution to these issues might not be to increase the population of doctors; doing it without a systematic plan may result in the decline of healthcare quality and end up achieving nothing meaningful. In this month’s Debate, we discuss whether expanding the quota for medical schools is the best option South Korea has.

The recent move of the South Korean government to gradually increase the quota of medical school admissions has thus far been met with a mix of support and disapproval. This is spurred by recent cases of critical patients in rural areas being denied services in hospitals due to a lack of personnel. Although a recent survey conducted by the government shows that most of the 40 medical schools around the country support an increase in the quota, the Korea Medical Association (KMA) has otherwise criticized the survey for being self-serving to the government’s intended outcome and threatened mass-wide protests should the government proceed with the planned increase. A similar plan was put forth by the previous Moon Jae-in administration to establish more medical schools in the country — a proposal equally met with blowback from the KMA through protests, eventually resulting in it being scrapped.

The core sentiment of the KMA against these plans is that it only provides a band-aid solution to a problem which is more systemic. There is indeed a shortage of doctors in South Korea, but the truth is that South Korea is facing a shortage of workforce in general; it is the main reason the government is gearing towards steps to attract foreign talent into the country. Simply increasing the quota could generate more influx of aspirants in medicine, but may affect interest in other professions that are similarly experiencing a labor shortage. Not to mention, this approach ignores the actual underlying cause of the problem, which is not the shortage itself but the skewed distribution of doctors nationwide. About a third of the medical schools in South Korea are located in the Seoul metropolitan area, some of which are the top medical schools that applicants aspire to get into. An increased quota will not guarantee that rural medical schools will receive an equal increase in incoming students.

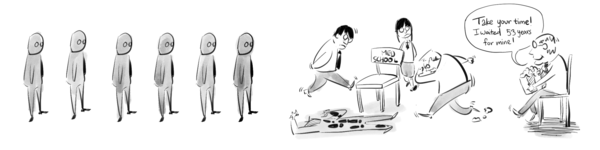

More importantly, medical school students prefer “lucrative” fields such as dermatology and plastic surgery. Especially since South Korea has a national health insurance (NHI) system that covers fees for mostly essential healthcare services, such fields still have a lot of room for other services not covered by the NHI, such as skincare and vitamin therapies. Meanwhile, fields like cardiothoracic surgery and pediatrics do not have much extraneous services to offer that cannot be covered by NHI, and therefore are less lucrative. Furthermore, such fields that involve complicated life-or-death surgeries are more prone to lawsuits and malpractice claims, making medical practitioners more hesitant to go to these fields.

The reality is that a revised quota for medical schools is not a sufficient, standalone solution to the problem that South Korea faces, and it will simply enable this problem at a larger scale, with more aspiring doctors seeking more lucrative and safer fields in the metropolitan area. More structural solutions need to be considered, and the government seems to acknowledge this; they have recently mentioned additional incentives and compensation benefits for doctors. This may be helpful, especially if they channel these efforts towards more critical, life-saving fields that are otherwise less enticing.

At the same time, it makes much more sense that the distribution of students across the country, rather than the quota, is managed to encourage the practice of medicine even in the rural areas. Policies that require a number of doctors to serve in particular areas of the country may resolve the localized shortages in rural cities. The prices of services for life-saving fields may also be tweaked accordingly to attract more doctors to specialize in these fields. I believe this will be a more difficult feat, given that the accessibility of important health services is a strong characteristic of the South Korean healthcare system, but there should also be efforts to improve the financial prospects of such fields. Such solutions are more practical and tangible to address the problems faced in the medical community.