The Facebook Papers and What It Means for Social Media Regulation

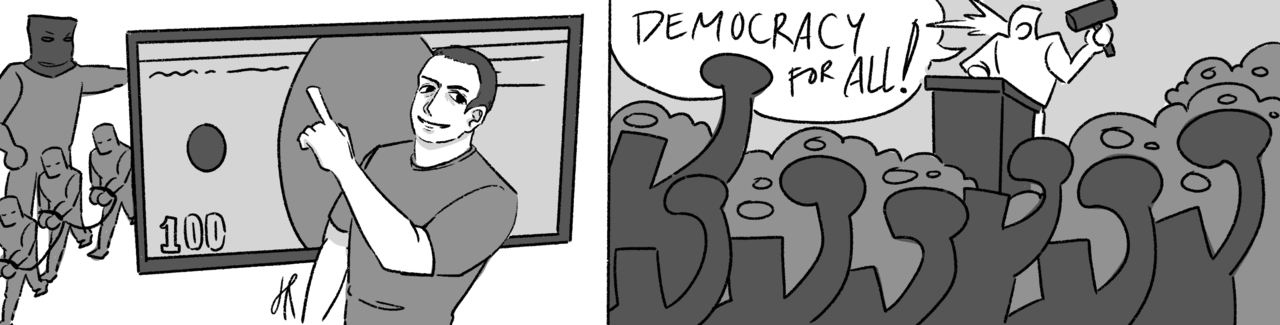

The Facebook leak by whistleblower Frances Haugen has exposed something most people knew all along: that Facebook prioritizes profits over user safety. Governments are now seriously debating new laws surrounding social media regulation — but is this a necessary solution, or just another power struggle?

We have talked about social media before — how ubiquitous its presence is in our lives, how the rise of trolls and fake news warn us to be more careful, and how it is harming our society. With the release of the Facebook Papers and Frances Haugen’s testimony as a whistleblower, we now have concrete proof of the danger of social media’s unchecked power. And we are reminded, now more than ever, that these platforms need to be reined in by regulations to ensure that they operate ethically.

In early October, Frances Haugen, a former Facebook product manager, released documents from Facebook’s own research and network detailing the harm it knowingly caused in pursuit of profit above anything else. Dubbed the “Facebook Papers” and first published by The Wall Street Journal, the revelations included the company’s research on Instagram and its negative effects on teenagers, weak responses to human trafficking and ethnic violence, and the principal role of politics and profit in the company’s decision making. None of these are surprising — Facebook (now rebranded to Meta) has been embroiled in scandals before, and many are aware of the company’s profit-driven operations. But Haugen’s testimony marks the first time that someone from inside the company has come forward with detailed evidence and has stated that the company needs to do better. It has also sparked discussions both inside and outside the company about its flaws and mistakes. Haugen’s whistleblowing may be what starts the long-overdue regulation of big social media platforms such as Facebook.

Although conversations about social media regulation have been ongoing for at least five years, we are only just starting to see them materialize into strong legislative measures. Even so, there is an abundance of criticism and fear on whether and how much tech regulation is appropriate and necessary — especially by governments. The Internet’s growth, after all, has been spurred precisely by the lack of government interference. One of the main reasons for the elusiveness of social media regulation lies in its fundamental difference from traditional media platforms: social media has near-unlimited reach and a lack of editorial oversight. Thus, most of the responsibility to choose what content to consume has been placed on the users. This makes the fine line between regulation and freedom of expression difficult to find. Self-regulation by social media companies themselves has faced scrutiny — for example, Twitter’s decision to ban Trump’s presidential accounts. But as evidenced by the deadly consequences of the spread of fake news during the pandemic, doubts about self-regulation and the lack of oversight have surfaced.

Around the world, calls for external government regulations for social media have been growing louder. A landmark legislation proposed in the UK imposes responsibility on tech firms “that allow users to post their own content or to interact with each other”, meaning that companies will face fines if they fail to protect their users from harmful content. In the European Union, a new law called the Digital Services Act is currently being debated, which strictly limits illegal content and requires companies to be more transparent with their algorithms. Haugen’s testimonies encourage these regulations, calling them a “game changer for the world”. The next step to government legislation is an internationally recognized body that will regulate social media platforms to limit their harm while protecting freedom of speech. This will eliminate the fears of governments controlling social media while involving experts on tech and social media for a more informed and feasible solution. It will also prevent companies from simply moving operations to countries where they won’t be regulated.

The Facebook Papers have shown us that internal regulations will never be enough. Private companies will undoubtedly place profit above all else — it’s their main business model. The potential harm that will always come with this ethos is what we have seen growing in the past few years: increased polarization, negative impacts on mental health, and even threats on democracy and human rights. As long as these companies continue to operate in a black box, their algorithms and decisions not accountable to anyone else, the same problems will appear and amplify in the years to come.

관련기사

- A Break from Instant Society

- With Great Power…

- Social Media Censorship: A Threat or a Necessity? - A Problematic Shortcut

- Social Media Censorship: A Threat or a Necessity? - Eliminating the Dangers

- Curbing “Fake News” and Where the Government Should Draw the Line

- Beyond the Pandemic: Tackling the COVID Infodemic

- [2021 November Society Debate] Social Media Belongs To No One

- Democracy or Regulation